Navigating the Camino and Climate Complexity

By Alexander Verbeek

The Planet, 9 August 2023

An hour belated, the clock strikes nine, and I am enjoying my first cafe con leche on the small terrace of La Casa del Abuelo on one of Madrid's bustling avenues. A sign reminds visitors that the House of the Grandfather has served its clients here since 1906. Cars race by, and the sun is gaining strength. An old woman in flowery dress walks by, using her stick as if sweeping the pavement.

I take a selfie in the large mirror at the cafe's entrance. Between the big painted letters recommending grandfather's wines, I see the weathered bearded face that I slowly got used to as my own during the many weeks of following in the footsteps of millions of pilgrims who have walked The Way for 1200 years.

But the pilgrim look is changing. I wear a new white shirt from El Corte Inglés and even combed my hair; I am transforming out of the Camino life into normality on a planet where that word increasingly causes confusion.

Extreme weather events are, by definition, unusual. But their frequency and severity are so rapidly increasing that a climatic system where that change happens is often referred to as the new normal. And however extreme and frightening the choice of this term may sound, it sadly isn't good enough to describe how bad our situation is. It suggests we have reached an unwelcome but stable end situation as if it can't get worse. But it will.

Perhaps millions of years from now, or much sooner, the planet will be okay again. It will still be swirling around the sun, traversing the universe's endless, dark, and cold nothingness while hosting complex life forms we can't yet imagine. One new intelligent species will become dominant; let's imagine some mutated form of octopus that looks like Barbapapa.

Some bright minds in their ranks will study that ancient life form known as humans and the sixth great extinction, similar to how our best experts are piecing together all clues they can find about the age of the dinosaurs. They will wonder how we humans knowingly destroyed ourselves.

The "knowingly" part fascinates them, and even more so when they realize we had the knowledge and means to prevent this from happening. Why did humans let this happen? Where was the desperation? The anger among the population? Or, more likely, they will ask how these humans believed they were so intelligent while sitting on the wrong side of the branch they were sawing off.

I fear how this thought experiment may end. Based on my experience, I expect these bright minds, millions of years in the future, to type a report to their leaders, describing the lessons learned from humans, that odd species that caused a massive extinction event that ultimately wiped themselves out. They warn their leaders that errors of the past may be repeated. I imagine their leaders ignoring the experts' recommendations; they prioritize short-term goals and are distracted by powerful lobby groups falsely claiming that the experts are mistaken and should not be listened to.

You get the picture; I'll stop here. You can fill in the rest because you know the scenario. I feel sad for these yet-to-evolve Barbapapa sapiens and fervently wish they will have a better form of dealing with fairness, scarcity, and greed than we came up with.

Just before taking my table at the grandfather's place, a screen in the hotel's elevator tells me it will be hot today, and in a few days, it will even be sweltering at 43 Celsius (about 110 Fahrenheit). But in air-conditioned Madrid, it doesn't hurt me like it would do on the Camino. Here, entering a shop or hotel lobby is all it takes to ignore the perils of a warming planet. But a few weeks ago, when walking on northern Spain's flat and dry Meseta, dealing with the increasing heat required careful planning. For instance, with these weather conditions, I would have started walking exceptionally early to be out of the sun before noon.

In Madrid, I enjoy luxuries I didn't have or searched for on the Camino, and briefly enjoying a different lifestyle in Spain's capital reminds me that on this warming planet, wealth keeps you cool. The rich can afford to pay for adaptation and continue living how they are used to, while the poor have to change considerably how they live their lives, and increasingly where they can live, to survive the new conditions.

That is true for individuals as well as countries; a situation that is not only unfair, it is also dangerous if the rich countries that are responsible for creating climate change are the ones least triggered to dramatically change their lifestyles and economies. Installing energy-consuming air-conditioning isn't a cool solution to turn off the global heating switch. Worse: it removes a trigger for urgent action.

I'm therefore pretty sure there is air-conditioning in each of the headquarters of the world's leading fossil fuel companies; there is method in the madness of pumping oil to keep cool, including insulation from the heat your actions have created. Trying to get your work done in a hot office may trigger unwelcome thoughts of turning down the global thermostat. But when you measure success by the shareholder value created, you shouldn't be distracted by the other impacts of your activities.

My morning coffee at Grandfather's reminds me that my second Camino venture concludes its chapter even though it must still be written. After I arrived at Saint James's city under the stars on the rainy evening of July 28th, after a hike of 29 days, my peregrinations pressed on. The next morning, it led me from Santiago to the rocky outcrop of Muxia and then onwards to Finisterre, where the world's best geographers once thought the world ended.

Today, we understand that our world as we know it will end, but we now try to capture its end in time rather than location. In Finisterre, the former end of the world was beautiful; I stood at the last rocks near the lighthouse and thought about friends and loved ones living beyond the horizon, where, unknown to ancient geographers, the world continues. It bakes in the sunshine after the sun sets in the waters beyond the horizon of Finisterre.

And in the world beyond the End of the World, they feel the heat too. In Canada, the eternal forests are burning to the ground at such a scale that the trees' ashes flew over the hot waters of the Atlantic and reached Spain on the same day that I crossed the Pyrenees mountains and the border into Navarre at Roland's Fountain, named after a legendary knight who served under Charlemagne and died fighting against the Saracens at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778.

June 28, 2023, Roland’s Fountain

According to legend, Roland threw his sword, Durandal, from the Pyrenees mountains to the Bidasoa River, where it landed and created a spring. And whoever drinks from the fountain will be blessed with courage and strength. So I drank from his fountain because we all need courage and a hefty dose of wisdom when the world we know is rapidly warming up.

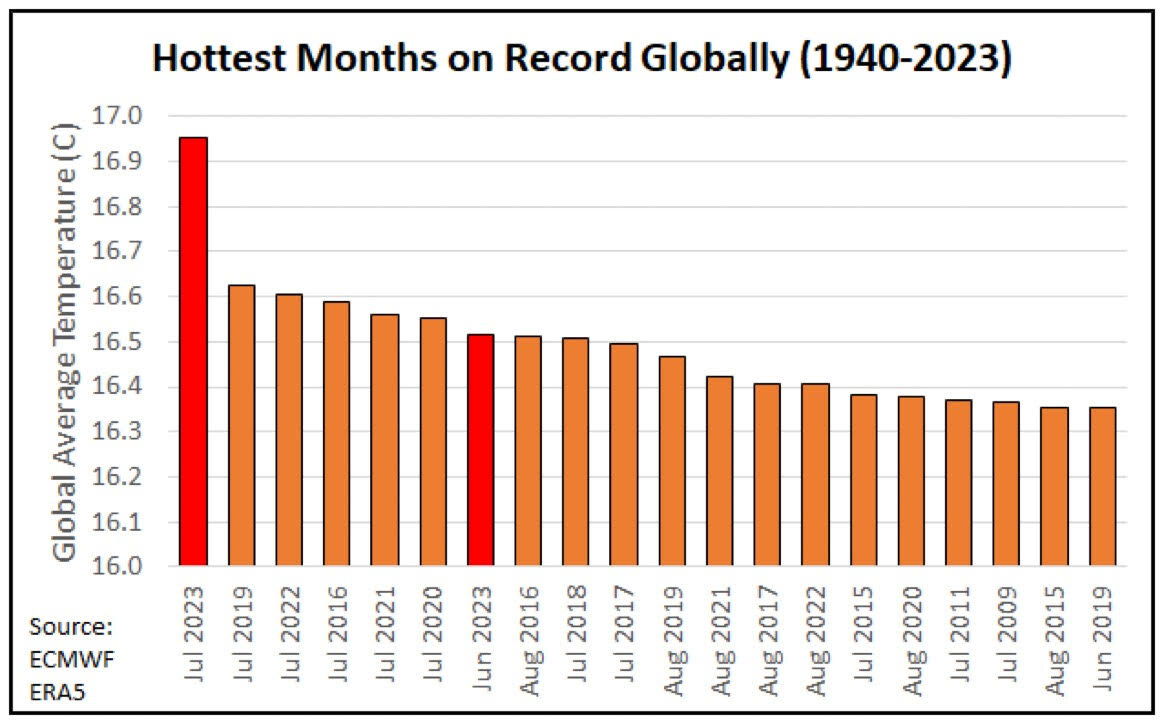

Little did I know that July 2023, the month I walked through Spain from Roland's Fountain to Santiago de Compostela, would become the hottest month ever measured on our planet. It was also the month that I collaborated with Swiss Re on the impact of climate change on the Camino de Santiago. The graph below, by Brian Brettschneider on Twitter, shows that it was a record-breaking month by a landslide, even though I remember shivering from the cold in the dense fog of the Pyrenees or in the morning rain when climbing up the steep path to the traditional mountain village of O Cebreiro, where its pallozas welcome you in Galicia. The cold served as a reminder that the weather can trick you into ignoring the climate.

source: Twitter, @Climatolagist49, Brian Brettschneider

Beyond the former end of the world, south from burning Canada, in the United States, extreme heat records are broken in many places. Phoenix, Arizona, just shattered its heat-wave record of 1974, with temperatures above 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43°C) for 31 straight days.

Next on a virtual trip southward through the New World is Mexico, the country of my Camino friend Santiago who walked at a remarkable pace to the city that bears his name. He lives near the border with Texas and shared stories of the increasingly hot summers in his country when we had dinner in La Vieille Auberge Chez Dédé the evening before we started our pilgrimage in Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. After weeks of walking, we later met again in Leon, where we were asked to witness a young American couple exchanging their wedding vows on the square in front of the city's beautiful Gothic Cathedral before we all joined for drinks in one of Leon's many cafes.

But we must go further south on the new continent to be even more astonished by what's happening in this record-breaking summer of 2023. Argentina and Chile are now in the middle of winter, but temperatures in some parts of these countries have soared to 10°C-20°C above average over the last few days. Several towns in the Andes mountains have reached 38°C or more.

City park in Porto, Portugal

I returned to Santiago from the end of the world with new friends made and interesting music recordings that I still want to share with you. The next day, I traveled by train and bus to Porto, where I loved to get to know this city and its history but missed the camaraderie of the Camino. But luckily, quite a few Camino friends had come to Porto too, like Santiago, whom I had last seen weeks before in Leon; we shared the stories of our long journeys during a memorable evening in Nola Kitchen. From there, I took a painstakingly slow train into Spain that, after eight hours, hardly moved my gps-locator much further from Porto. It was only in the late afternoon that I finally connected to Spain's famous fast-speed railway network that brought me at a speed of close to 300 kilometers per hour to the heart of Madrid.

Six weeks of travel have given me a collection of untold tales, countless memories to hold dear, and a gallery of photographs to immortalize the voyage. But this is no terminus, and there will be more stories to share. Today, the island beckons, but this summer also holds the promise of visiting Belgium and France, and soon after, Switzerland looms on the horizon.

So you may wonder, does the 8:00 a.m. challenge of sharing a photo of where I am at that moment end here? It was conceived for the Camino and for the Patreon platform. I have posted every day and occasionally used my Substack newsletter instead of Patreon to post to you. And now that this article has grown longer, I will likely paste this one into the Substack format too. The Canadian winter may make me hesitant to continue, but if you enjoy these posts, I may send a few more in the weeks ahead before a long hibernation of this project.

Thanks for all your support that made this journey possible, and stay tuned for this chronicle continues to unfold a bit longer. So much is changing on our planet, and so much more should change soon, that sometimes continuation is preferable; if you agree, writing about my morning's experiences and thoughts on Patreon or in the Substack newsletter may be one of them.

Drinking a morning coffee in Grandfather's cafe in Madrid is another of my morning memories; it is also a tribute to what the generations before me have done for over a hundred years. We live in a time where we need both radical changes and continuation; it is another of the dichotomies I have referred to in earlier writings. Our challenges are complex, and sharing insights helps us to collectively navigate the storms we face.

This grew longer than I had planned; it is now late evening. Thank you for staying with me until the end, a challenge even for Santiago when sleep beckons. Comments are always welcome; you can use the button below. Or click on the other buttons to sponsor my work by buying me a coffee or joining the small group on Patreon of loyal supporters with more access to my work and whereabouts.

>>> Read more articles by Alexander Verbeek in The Planet

The popular newsletter for you and all those that love our fragile, beautiful planet. Start your day with independent writing on climate, wildlife, oceans, and the beauty of nature; often combined with historical anecdotes, art, and travel stories.